(facsimiles of hand-written memoires part 1, part 2, part 3)

Transcription:

10th October 1914 - Wedding of Miss Lizzie Checketts Wilson (Elsey) and David Bain

Standing: Uncle Bob (Robert Bain groom's brother 11/2/1888-23/7/1976), Aunt Dorothy (Dorothy Jean Wilson bride's sister), Mum (Bride 3/3/1891-25/1/1963), Dad (Groom 18/11/1880-31/10/1961), Uncle Alex (Alex Bain groom's brother 9/6/1877-21/1/1951), Aunt Bella (Isabella Findlay Bain Groom's sister 23/1/1872-?)

Seated: Aunt Maggie (Margaret Bain groom's sister 21/3/1875-29/7/1964), Grandpa (William Thomas Wilson bride's father), Granny (Elizabeth Checketts bride's mother), Uncle Andrew (Dr Andrew Taylor husband of Aunt Maggie)

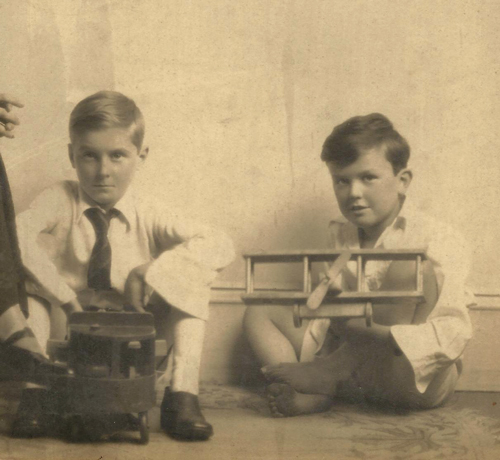

I was born in Craven Avenue, Ealing W5 on 30th June 1915: and two years later on the 1st of June my brother Keith Alexander arrived.

My father David was serving in France in the Royal Engineers it is rumoured that he had a special interest in the carriage of messages by pigeons (his father Alexander was a well known pigeon breeder in Kirkintilloch).

After the birth of Keith it was decided that two young children were too much for my mother to cope with and I was transferred to the care of my maternal grandparents (Wilsons) who lived at Glenlea, Church Road, Roby Nr Liverpool. I rather enjoyed the country life and a large garden which tended to despoil much to Tom’s (the gardener) chagrin.

My grandfather was constantly purchasing bits of the surrounding farm land to prevent development. The farmer was a Mr. Revell who was a tenant of Lord Derby and his Knowsley estate.

Groceries came from Liverpool on Thursday in a horse drawn van and the milk arrived daily in a float on which I sometimes got a precarious ride.

I went to school in Huyton walking the mile or so in all sorts of weather by different routes to ring the changes (occasionally I went by train from Roby to Huyton but this saved very little in walking distance).

I was most impressed when walking down Dale Street, Liverpool, with my grandfather, to observe a man drop to the ground with a fountain of blood spouting from his mouth. I was told he had burst a blood vessel. (?aortic aneurism – Syphilitic I expect).

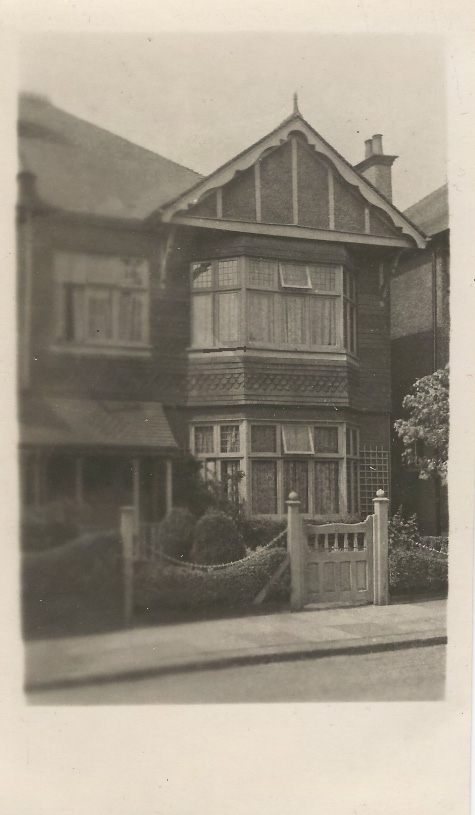

Soon after my grandfather’s death in 1924 (of diabetes - Banting and Best discovered insulin in 1922) I joined Keith and my parents in Ealing living at 46 Denbigh Road (Arrandene) until 1954. The semi detached house cost the exorbitant sum of £750.

Brother Keith seemed to have a problem with reading and he must have been eight or nine before he mastered the process and devoured books at an ever increasing tempo.

We both attended Durston House School in Castlebar Hill – about a mile from home. An excellent prep school with a good academic record presided over by a strict disciplinarian Ben Pearce. Opposite the school was a local G.P. with two sons the same ages as us. They had an unfair advantage in the morning in that they could set out from home at the first note of the morning bell. One son became a doctor and the other a solicitor. I was to meet the doctor again at St. Mary’s Hospital where he was medical superintendent for many years.

Apart from the occasional foray against the “Green Boys” (Roman Catholics from St. Benedict’s Priory) life was uneventful although my athletic prowess reached it’s peak at Durstan House where I held the record for the high jump and was Victor Ludorum in 1928 winning the 100 and 440 yds as well as the high jump.

In May 1929 I went to St. Paul’s School (Kensington then) and soon found myself on the "Army" Side possibly because it was part of the "senior school" with a half day on Wednesday rather than the Thursday and no IV form just V, VI, VII and VIII it was possible to be in all four at the same time dependent on the subject. An excellent idea as the better one was at any particular subject the higher in the school one was placed – and vice versa. I left in July 1932 with my "School Certificate" and the necessary credits to achieve matriculation if necessary. I had a desire to go into the Navy but my father was very against it.

In the summer of 1939 I was a final year medical student (along with about 30 others - all male and single, of course) at St Mary's Hospital Paddington.

At the outbreak of war groups of us were sent to reinforce the sector hospitals and I found myself with John Friend at King Edward VII hospital Ealing (convenient for my parents home in Denbigh Road) attached to Douglas McLeod an eminent but rather pessimistic obstetrician and gynaecologist. As nothing much happened we soon return to St Mary's and got on with our studies (though at some stage we spent a lot of time filling sandbags).

Most of us sought the glamour of the Armed Forces and although on degree courses, elected to take the conjoint examination six months earlier.

Armed with an MRCS, LRCP I attended an interview for the post of house surgeon at St Mary's - salary £35 per annum all found. This particular appointment was to V. Zachary Cope and R. M. Handfield Jones. I was asked about the treatment of shock and having given all the usual methods, they still seem to want something more. In desperation I suggested ministering rectal champagne. Cope (a Quaker and teetotaller) thought this was the best way to give it but H-J (a bon viveur) said "what a waste Laddie". However, I got the job, which included dancing attendance on Lionel Colledge (an E.N.T. surgeon and father of Cecilia the ice skater) I got a false impression of the speciality as, because of bed shortages the only operation performed was the horrific total laryngectomy. After this unpleasant procedure the voiceless patient had to learn to communicate by belching through his tracheotomy tube. Suicide was a not infrequent complication. House surgeons were not expected to take time off and the hospital was of course on a "war footing". Much of the routine work had been transferred to the peripheral hospitals which at that time were manned by GPs each specialising in a particular subject.

After six enjoyable months I moved on to become "casualty surgeon". Roger Mills was the other incumbent as we were both on duty in the mornings (the busiest time) and alternated the shift from midday to 9 a.m. I think the weekends had a different pattern. Five days a week we had the assistance of a Casualty Physician from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Ambulance casualties were not all that frequent and much of the workload consisted of septic hands. Sulphoramides were available but penicillin (discovered over the road) was not yet available (the pianist Solomon frequented St.Mary's and befriended Fleming who used early penicillin to cure his septic hand). About midday, minor surgery was performed under general anaesthetic. When the "Battle of Britain" began the work pattern changed and although excused fire watching activities on the hospital roof, there was little off duty time. When aerial activity in the Paddington area was absent we were sometimes drafted to busier sections of London.

(H.M. the Queen visited the casualty dept. and I had to present the dressers. One R.G. Laurie insisted on saying a few words accompanied with his stutter and jactitation.)

I remember early one morning stitching the face of a man who had tried to jump under a bus. Later on that morning a b.i.d. (brought in dead) arrived on a trolley with the severed head at his feet covered with a blanket. I was horrified to see the sutures of the early morning. This time a tube train had ended his life (his wife and two children had been killed in an air raid during the night).

When the battle was won I decided to try and join the Navy which was medically replete while the RAMC was short of recruits. Besides this I was now a member of the EMS (emergency medical service). Fortunately my father was on friendly terms with one of the Sea Lords and the Medical Director General put in a special request for my services. This was granted and in November 1940 I got posted for admissional course at Chatham Barracks.(RN application references).

Before going to Chatham I got kitted up at Gieves and was so pleased with the result that I went prancing down St. James'. Of course this was the territory of high ranking naval officers and my experience of saluting was restricting to my days in the X Chelsea (St. Columba's) troop of Boy Scouts. However I got by somehow. The gold Navy braid with the scarlet inset went all the way round the sleeve. Shortly afterwards as an economy measure only the outer half of the sleeve was so decorated.

Chatham Barracks was my introduction to the Navy with four or five other temporary probationary (six months) Surgeon Lieutenants RNVR. There was a gaitered Gunnery Lieutenant to put us through our rather miserable paces on the parade ground and some retired Surgeon Captains RN to lecture us on general principles. We discovered that these lectures ended promptly at 11 a.m. to enable the elderly gentlemen to imbibe sufficient gin before lunch. The main thrust of these talks was to assure us that we were carried at sea for morale purposes and that the likelihood of our being of any use was remote. Some of the old cliches like getting the ships company into clean underwear before going into action were trotted out but I was impressed by the self-effacing attitude of never doing anything to draw attention to oneself, never signing anything and never appearing on deck without a sheaf of papers under the arm and in a hurry.

At Chatham we learnt about the quarterdeck (a rather insignificant patch of grass in this instance) liberty boats and all the other jargon that was to become our every day language. Announcements over the tannoy system were also to become a way of life. These were preceded by a note or two on the boson's pipe. "Duty medical officer to sickbay to examine survivors" was something of a surprise the first time I went expecting to see bedraggled specimens with seaweed attachments. Nothing of the sort, these were men whose ships may have gone down weeks or months before and were merely being checked to see that they were fit for a spot of home leave. Injured personnel would have filtered through the naval hospitals.

One of the group was John Richardson (subsequently Consultant Surgeon at the London Hospital). He had passed the FRCS (Eng) exam but was not allowed to "use it" until he was 24 - an event that occurred during our sojourn at Chatham.

We were rather jealous when he was posted to the brand new Prince of Wales. It was said that Churchill, who was to take a trip in her to meet President Roosevelt, looked through the proposed medical compliment and noted there was no one with an FRCS and complained hence Richardson's draft.

Not long after the Prince of Wales and Repulse were to be sunk by Japanese air attack off the coast of Malaya. Richardson managed to step onto one of the escort destroyers and didn't even get his feet wet. The incident certainly aged him and he would never talk about it.

It so happened that John Friend, who qualified with me, join the RAMC at the same time as I went into the Navy. The reason he gave was because he was prone to seasickness. This must have disturbed him when his first appointment was to a troopship. His holding area was at nearby Gillingham and he asked me to a mess dinner which was eaten off upturned packing cases in a council estate. I was able to return the compliment at a mess night at Chatham with the silver, gloved stewards etc and the inevitable rounds of port for infringements of protocol. Friend was quite overcome by the magnificence of it all.

Chatham was my first encounter with port and I found it so potent that even going into the fresh air onto the quarterdeck I thought we were at sea. I don't suppose that we spent more than a couple of weeks or so at Chatham although it seemed quite a long time.

There was a commander Pankhurst supervising the refit of his new command an F class fleet destroyer Fortune. I played squash with him and he asked me to be his MO, as he was listed as a Russian interpreter I agreed and ratification was obtained. In peace time only the flotilla leader carries a doctor, but wartime brought some profligacy to the scene.

HMS Fortune of the Fearless Class was completed in 1935 (Fame, Fearless, Firedrake, Foresight, Forester, Fortune, Foxhound and Fury) 1350 tons 323 feet long four 4.7" guns, 8 tubes plus oerlikons etc. 34,00 S.H.P. Speed 36.5 knots. Compliment 145+. Radius of action at 15kts 6,000 miles. Penant no. H70.

As the Fortune was refitting in Chatham dockyard I was able to visit frequently and had I been experienced I could, no doubt, have a range modifications and additions. As it was I persuaded one of the "chippies" in the dockyard to convert a solid packing case into a receptacle for my personal belongings. It had thick rope handles and was tastefully labelled with my name and rank outside RN environs it was to prove a handling problem.

The ship's company was for the most part inexperienced apart from the officers, and many had never been to sea before. The captain, related to the suffragette, came of a military line and his escape to the Navy was not regarded with much favour. He had several tiresome eccentricities – including a determination to acquire a posthumous VC.

The Engineer Officer was a 2 1/2 RNR (from the merchant service) supercilious and pessimistic - no jokes ever passed his lips but he was a passionate about his machinery and cursed (under his breath) the captain when excessive demands were made upon it.

The first lieutenant was perpetually worried and does not seem to have made much impact on my memory. The navigator – as sub-lieutenant was very pleased with himself and I know I christened him Vasco for some fancied discrepancy. The other day I came across a recently written piece by him and can therefore give his proper name Roderick Macdonald. I was surprised to note that he became a Vice Admiral and a KBE (not bad going – considering the post war weed out).

The paymaster and the others are hazy recollections.

The Fortune, not being a flotilla leader, had no cabin for the MO and I dossed down in the sickbay which was at main deck level on the port side of the bridge superstructure. Instead of a bunk there was a cot in gimbals which was very comfortable but had to be vacated when it contained a patient.

Two incidents of a medical nature occurred early on in Fortune:

I have, perhaps, always been a small pint chap and I noted that MOs should periodicly check the eyesight of certain key ratings – thus it came about that I carried out an eye test on the Petty Officer Gun Layer and found it deficient. He had to be replaced and I felt a heel.

The Captain's Steward was apt to disappear into the bowels of the ship at the sound of gunfire Cdr. Pankhurst thought he knew the cure and I watched in some amazement as the unfortunate Steward climbed up to the bridge balancing a tray of edibles closely followed by the stealthy Captain clutching a rifle. Just as the Steward reached the bridge platform the gun was fired – the tray was dropped and the Steward returned at high-speed to his quarters from which no amount of cajoling could prise him out until he was relieved at the next port of call.

I mentioned that destroyer crews were selected for the high degree of fitness and perhaps to get rid of a brace in a short time was unusual. The stokers - of course- - were comparable to the brass section in an orchestra, and were a rough and unpredictable group. I have never been able to fathom how it was that I seem to "gel" with them!

Besides my clutter there was plenty of equipment for amputations and the dispensing of exotic coloured medicines and tablets. Only the young and fit were drafted to destroyers though venereal disease was unfortunately no bar.

No doubt there were sanitary arrangements and although I was required to inspect them with the captain on routine rounds I have no memory of the heads.

In due course we slipped for working up trials. The previous night mines had been sewn by enemy aircraft. Mines were essentially of three types. WW1 ones with horns moored below the surface, magnetic (for which we were degaussed by having an electric cable wrapped around us) and acoustic which were triggered by the ships screws. On this occasion the magnetic variety was in use. We were preceded by a pair of mine sweepers, but the captain got bored by the slow speed (6 or 7 knots) and signalled his intention to dispense with their services. We forged ahead and very shortly detonated of mine. The explosion lifted us out of the water but didn't appear to do any other damage.

Shortly after this the captain exhilarated by his new command announced his intention to carry out an offensive sweep off the Dutch coast. C in C Nore thought otherwise and signalled tersely "carry out original orders".

Night fell without any further excitements apart from the sea becoming more choppy, until about 22:00 when we were told an enemy E Boat attack was imminent. Almost simultaneously a torpedo passed astern. Pandemonium broke out and most of our guns seem to open up at the shadowy E boats who turned and sped away. I don't think we inflicted any damage except on ourselves – our guard rails were shot away! Somewhere off the north east coast of Scotland I confidently identified the Scharnhorst at extreme range (One of my many extra duties was ship's identification officer. I was not supplied with any medical books, but I did have several volumes to help in this particular task). However I soon had to alter my opinion to a tug towing a floating dock. I was not officially criticised as Admiralty should have informed us on this particular one.

When we had our shooting practice with a drogue towed by an aircraft we were quickly told to ceasefire as our bursts were nearer the aircraft than the target. In Londonderry our gun alignment was checked. It appeared that the mine incident in the Thames estuary had twisted our stem and compensation had to be made for this.

We had an Irish pilot at Londonderry and gave him a drink in the wardroom. He had two remedies for seasickness a tumbler full of sea water or of whisky. Another of my duties was to supervise the food and drink in the officers' mess. Not well qualified for this at all.

Moving from sickbay to wardroom entailed a journey along the exposed deck clutching (in bad weather) the "safety rail" and trying to judge the optimum moment for a dry passage.

I often met submariners who alone in the Navy referred to their craft as a "boat" and we discussed the dangers inherent in the respective receptacles. Just as those in destroyers rejoiced in their comparative safety so did the submariners and the arguments ended in each being content with their lot.

Next to the Denmark Straits (Aug-Nov 1941) after the humiliating experience of escorting the Queen Mary to the 500 mile limit and watching her draw ahead, as the heavy seas forced us to reduce speed, with a curt "many thanks now I must leave you". Patrolling in the Denmark Strait (between Iceland and Greenland) to intercept commercial raiders was distinctly uncomfortable.

It was never light, always below freezing, and the seas were mountainous. The galley stove was out and even hot drinks quite difficult. We didn't do much "pinging" for U-boats and radio traffic was light (cipher officer was another of my duties). We didn't communicate with each other more than was necessary and only did what we had to. I suppose we lived out of tins and vitamin tablets. Just before Christmas (Dec 1941) we were told to join Force H at Gibraltar. What joy. After the northern climes the warmth and sun seemed like paradise and fear of death returned to our numbed minds. Fresh food and runs ashore made us happy and cheerful. By the end of 1941, 8 outward convoys - no losses.

At that time radar (radio detection and ranging) was coming into use. On the top of the rock was the equipment to scan the Straits of Gibraltar. We would slip at nightfall and intercept any vessel that had been located, returning at dawn - this was most satisfactory and quite a popular duty. Circling the contact once or twice to attempt to identify it with flashes of searchlights or star shells and when necessary boarding and searching. A cargo of the Zeiss cameras and binoculars was a tempting occasion.

Another popular routine was the Trafalgar - Spartel patrol to try and prevent enemy submarines (German and Italian) passing through the Straits. Weather was usually good apart from a heavy swell always on the beam. Once we had to refuel in the Canaries (neutral) and pay in cash. We also stocked up with eggs and bananas. On the way home we intercepted a French fishing boat and swapped cigarettes for lobsters etc. The C.in C. wished to know why we hadn't brought her in - "impracticable" was the curt response.

It was thought that a few WRNS would be a pleasant addition to life in Gibraltar. Unfortunately an attempt to import a dozen also on a routine convoy was unsuccessful. Convoys were routed far out into the Atlantic to put them outside bomber range. U-boats however were in menace. It was then decided that Force H should go to the UK to collect the WRNS and give 24 hours leave to each watch. Fortune and one other destroyer remained at Gibralter. Normal duties were suspended but we took it in turns to be "stand by". On one such occasion we were suddenly told to raise steam and report when ready for sea. Next came instructions to put all confidential books ashore and land unnecessary personnel (who ever they may be!) We thought that a trip to the beleaguered island of Malta was our most likely destination. However on leaving harbour we turned to starboard and went out into the Atlantic through the Straits. At about 02:00 a signal to return to harbour was received. It transpired that RAF reconnaissance had notified the absence of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau from Brest and it was assumed they were off on a commerce raid in the South Atlantic. Fortune was to intercept but these heavily armed ships had returned to their base and all was well.

Malta was besieged and air defence depended on three ancient Gladiator aircraft. Fortune was dispatched (Jan/Feb 1942) with a Spitfire to augment this inadequate but heroic trio. Off Pantelleria in heavy seas divebombing Italians were troublesome and in evading a stick of bombs we heeled over until the sea cascaded down the smoke stack. Fortunately we righted ourselves but minus the deck cargo. Entering Valletta we felt a little ashamed as the cheers rang out. The passage from Gibraltar to Malta was more hazardous than Alexandria to Malta and we took part in one of the latter convoys in which four merchantman were surrounded by about 30 warships. Despite the massive escort I only remember two of the merchantmen reaching Malta. My memories of Alexandria are dim but the picture of a rather sordid place with the occasional body in the gutter is uppermost.

Cairo and the pyramids were visited but I cannot recollect now. Soon the time came to pass through the Suez Canal. A cockney steward who never came up on deck refused to come and look at the camels on the specious grounds that they could be observed more satisfactorily at the London Zoo!

The various calls over the tannoy system kept one in touch with the working of the ship:

"Afternoon Watchmen to dinner"

"Darken ship"

"Action stations" (at sea this call went out half an hour before dawn and again at dusk)

"Hands fall in for entering/leaving harbour"

"special sea duty men to their stations"

... and many more.

As we monotonously traversed the Red Sea it got hotter and hotter until we arrived at Aden. I didn't care for this spot one little bit but those stationed there seemed happy enough. I went swimming behind the steel netted shark barrier unlike some Australians who lept over the side of a troop ship and were instantly consumed. Perhaps some of my discomfiture was due to the fact that I only possessed north Atlantic clothes. This was to be remedied when we reached Bombay - such a long trip in the cutter from the Anchorage.

The Indian Ocean was mostly like a mirror and flying fish were plentiful. The coast of India was outlying and Bombay seemed to be built on a rather murky sea. We anchored a long way out and it took a good hour to make the harbour steps in one of the ships launches. India was dusty, dirty, crowded and smelly but I was able to get tropical kit of the finest cotton and twill. Six short sleeved shirts with detachable badges of rank, six pairs of white shorts, six pairs of stockings and a set of number tens. Laundry was a problem my SBA (sick birth attendant) dealt with mine after a fashion, white soon became grey. My SPA was called Crapper - not inappropriately – and was deemed of some consequence by his messmates as he had been trained at the same hospital as myself (Doc, sawbones, the leach etc.) St. Mary's Paddington. My new clothes were ready in 24 hours and cost in Annas and Rupees the equivalent of about £10. Life was certainly more comfortable and the addition of white buckskin shoes made a presentable sight.

The Tower of Silence made quite an impression - tall demes on which mortal remains well laid on wooden platforms for the vultures to pick clean.